Original article

Published in spanish Científica Dental Vol. 21. Nº 1. 2024

www.cientificadental.es

Correlation between the presence of sleep apnea and prosthetic and implant fractures. Series of clinical cases with identification of the process and treatment with mandibular advancement device

Introduction: The presence of dental signs and symptoms in patients with sleep apnea (OSA) that are recognizable to the dentist places us in the first line of diagnosis and subsequent treatment for patients suffering from this pathology. From problems such as wear and tear and fractures, we can reach a diagnosis of a pathology with great repercussions for the patient and address a crucial part of the treatment, such as recovering the vertical dimension and the use of mandibular advancement devices.

Material and method: We retrospectively recruited patients who attended our dental clinic with problems in different implant rehabilitations of an eminently mechanical nature (fracture of ceramics, prostheses, or components as well as implants) who underwent respiratory polygraphy to reveal the possible presence of OSA. In those cases where this disorder was found to be present, we selected patients with moderate-severe OSA (apnea- hypopnea index (AHI) ≥ 20) to analyze the different adverse events that occurred according to the severity of the sleep disorder recorded.

Results: Twenty-two patients who met the previously established inclusion criteria were recruited. Adverse events were identified in all patients in their implant restorations, these complications being fracture of the prosthesis ceramic (63.6%), structural fracture of the prosthesis in 18.2% of the cases (structure itself or resin coating in hybrids) and fractures or cracks in the implants in 18.2% of the cases. The mean AHI (apnea-hypopnea index) of all patients was 33.29 (+/- 18.90; range 20-110). If we analyze the presence of adverse events in the prostheses according to the AHI, we find that most adverse events are concentrated in the higher AHI ranges. A therapeutic approach with CPAP (continuous pressurized airway oxygen delivery device) combined with a mandibular advancement device (DIA) was used in two patients, the rest only DIA. With treatment completed, patients went from a mean AHI of 33.29 (+/- 18.90) to a mean of 17.38 (+-10.37), these differences being statistically significant (p<0.001).

Conclusions: Bruxism and OSA are closely related, as are the dental signs of both processes, such as wear and fracture of teeth, implants or rehabilitations. Dentists can be a fundamental pillar in the treatment of these patients, including the first step in the diagnosis of undiagnosed cases of OSA, which can be identified through dental problems.

Key words: Fracture; Bruxism; Obstructive sleep apnoea.

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is defined, according to the Spanish Consensus Document, as “a condition characterised by excessive sleepiness, cognitivebehavioural, respiratory, cardiac, metabolic or inflammatory disorders secondary to repeated episodes of upper airway obstruction during sleep”1. At present, it is a major public health issue which, in its most severe forms, affects 3–6% of men, 2–5% of women, and 1–3% of children, causing arterial hypertension and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease in those affected, as well as a consequent deterioration in quality of life, accidents, and excess mortality1,2. Early diagnosis is therefore of vital importance, as with appropriate treatment we can reduce patients’ symptoms and long-term side effects, substantially improving their quality of life as well as reducing cardiovascular events, which may have a fatal outcome1,2. At present, the correlation between

sleep disorders such as OSA and oral pathology, for example bruxism or fractures, of various rehabilitations, both on teeth and on implants, is widely documented today. This association has been demonstrated in several epidemiological studies over the years3-7, with our research group highlighting that the presence of dental wear in patients should prompt a thorough sleep analysis, as the degree of dental wear is directly related to OSA via the AHI (apnoea-hypopnoea index)9-11. This relationship is directly proportional, and it is confirmed that patients with more severe wear also exhibit a higher AHI, which is likewise associated with an increased incidence of fractures in enamel, dental roots, and prostheses. Mechanical events may,

in some cases, also affect implants, resulting in bone defects due to overload, and in extreme cases, leading to fracture of the implant itself.12-14. In the following clinical case series, we sought to retrospectively collect a group of patients who experienced adverse events in implant-supported prostheses associated with mechanical overload (fractures, loosening), to whom a subsequent polygraphic sleep study was performed, identifying those in whom these events could be related to the presence of OSA. The most severe cases identified (AHI ≥ 20) were analysed to obtain data correlating both events (OSA and mechanical complications).

Patients who attended our dental clinic retrospectively with problems in various implant-supported rehabilitations of a predominantly mechanical nature (fracture of ceramic, prosthesis or components, as well as implants) were

recruited, and respiratory polygraphy was performed to determine the possible presence of OSA. In cases where this disorder was confirmed, we selected patients with moderate to severe OSA (AHI

≥ 20), in order to analyse the different adverse events that occurred according to the severity of the recorded sleep disorder, during the period between January 2014 and December 2015. The primary variable of the study is the presence of prosthetic adverse events in relation to a moderate to severe OSA condition, analysing the type of prosthetic adverse event that occurred and its potential

relationship with the AHI. As secondary variables, an analysis was conducted of the approach taken for the treatment of OSA and the impact of this treatment both on the values associated with the AHI and on the occurrence of new adverse events once the treatment had been instituted.

A Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted on the data obtained

to confirm the normal distribution of the sample.

Qualitative variables were described by means of frequency

analysis. Quantitative variables were described

using the mean and standard deviation. The association

between the severity of OSA (AHI) and the occurrence

of adverse events in the prosthesis was analysed using

Pearson correlation analysis. Data were analysed using

SPSS v15.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

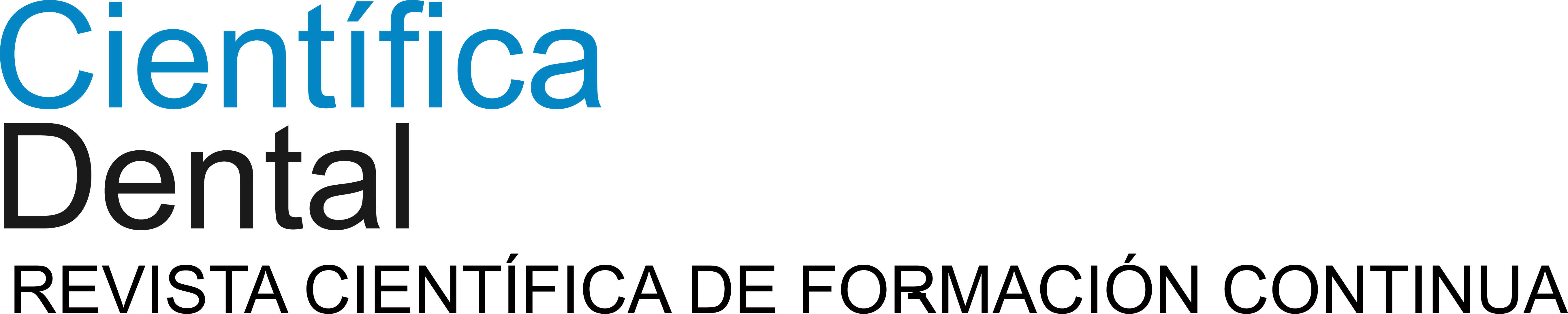

Twenty-two patients who met the previously established inclusion criteria were recruited. Of the patients, 54.5% were male, with a mean age of 64.55 years (± 8.06; range 46–84 years). Adverse events were identified in all patients in their rehabilitations with implants, with the complications being as follows: fracture of the prosthesis ceramic in 63.6% of cases, structural fracture of the prosthesis in 18.2% of cases (either the structure itself or the resin coating in hybrid prostheses), and fractures or fissures in the implants in 18.2% of cases. Fractures of the prosthesis and of the implants were observed equally among men and women, with ceramic fractures being slightly more frequent in the male group (Figure 1).

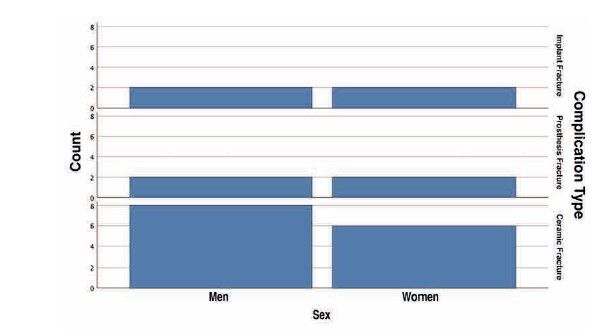

The location of the adverse event was predominantly

in implants placed in position 26 (18.2%), followed by position 16 (13.6%), with the first maxillary molars thus representing 34.5% of all recorded events. The other locations where mechanical incidents were recorded are shown in Figure 2. When grouping the events by maxilla or mandible, a higher incidence was observed in the maxilla, accounting for 68% of cases.

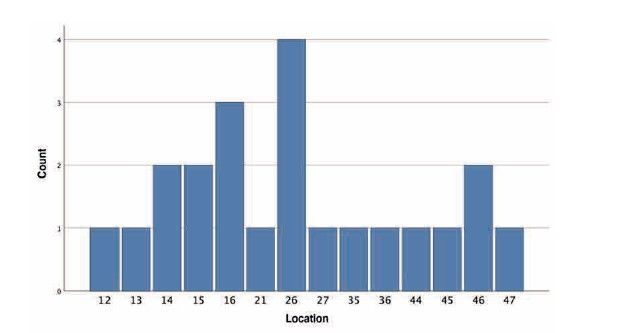

With regard to the type of prosthesis affected by complications, two-unit bridges accounted for 50%, followed by single crowns at 36.4%, and bridges of more than two units at the remaining 13.6%. Of the prostheses that experienced complications, 77.3% were cemented and the remaining 22.7% were screw-retained, with complications being more frequent in cemented crowns and bridges than in complete prostheses, as shown in Figure 3.

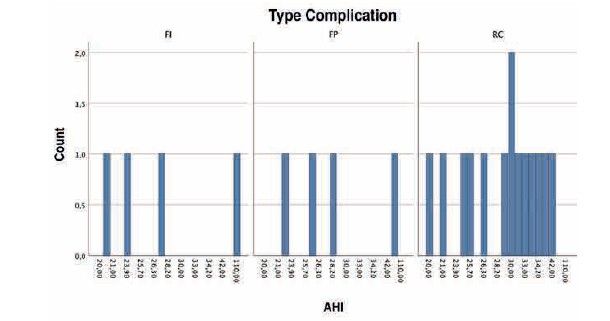

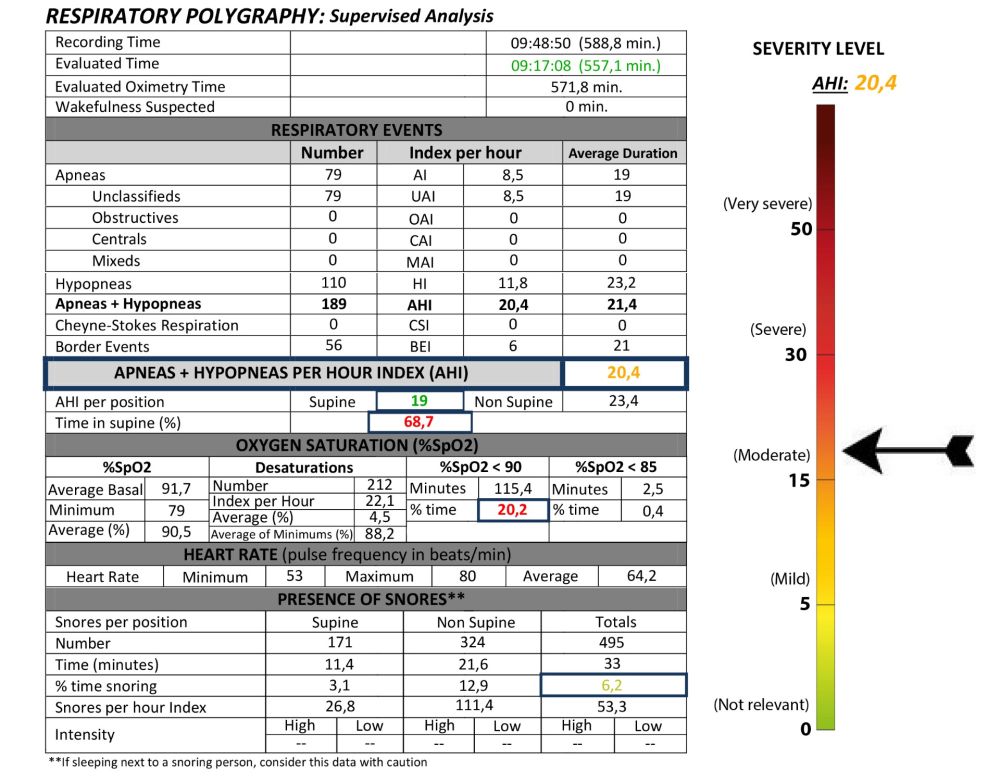

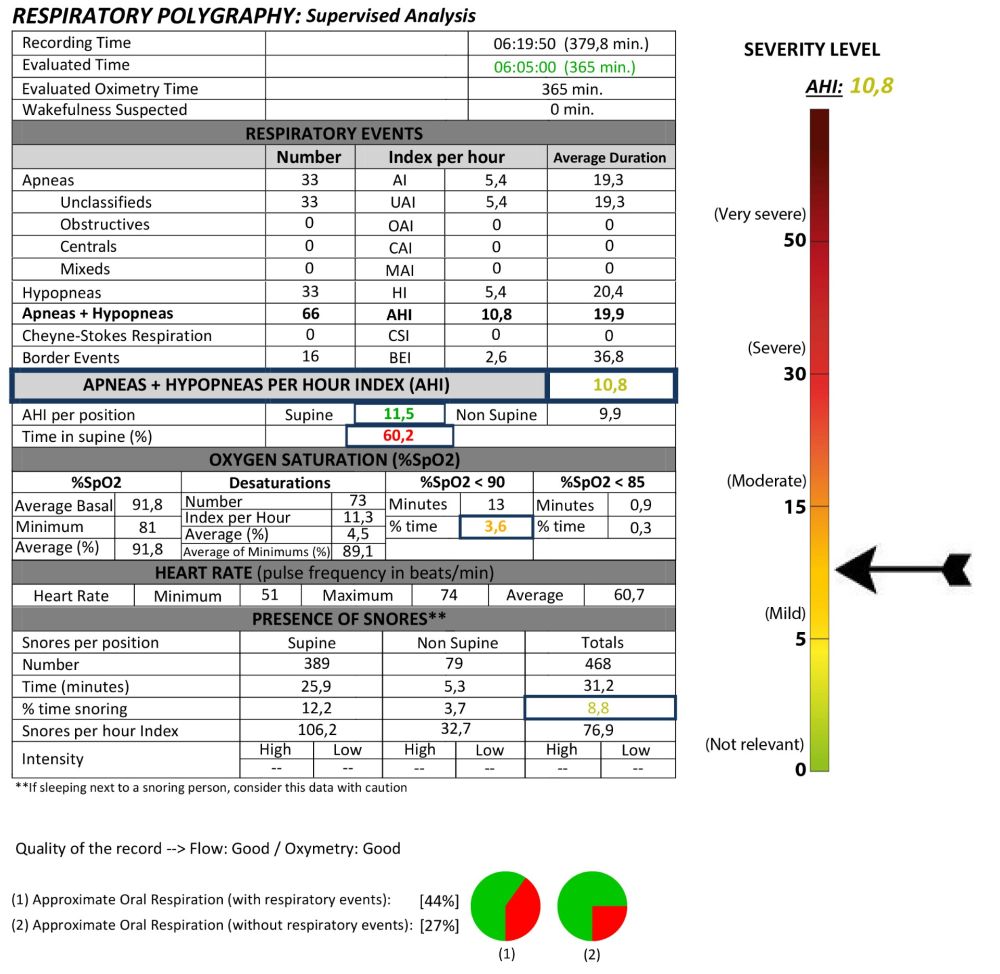

The mean AHI for all patients was 33.29 (+/- 18.90); range 20–110). If the presence of adverse events in the prosthesis is analysed according to AHI, it is observed that the majority of adverse events are concentrated in the higher AHI ranges, as shown in Figure 4, although no positive correlation was found between increasing AHI and the type of complication observed (p=0.432).

Once the respiratory disorder was identified in the

patients, the issue was addressed and treatment for

OSA was undertaken using intraoral mandibular advancement devices (DIA-Biotechnology Institute®), with CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure device) also employed in the most severe cases (2 patients). In all patients, a reduction in AHI was observed with treatment, with the device being adjusted in each case using the most effective tensioner and the minimal possible protrusion, monitored by respiratory polygraphy. Upon

completion of treatment with the MAD, patients’ mean AHI decreased from 33.29 (± 18.90) to a mean of 17.38 (± 10.37), these differences being statistically significant (p<0.001).

Patients were subsequently followed for a mean of 39 months (± 8) after completion of prosthetic treatment and placement of the MAD, not en no new mechanical prosthetic incidents or implant complications were observed during this period.

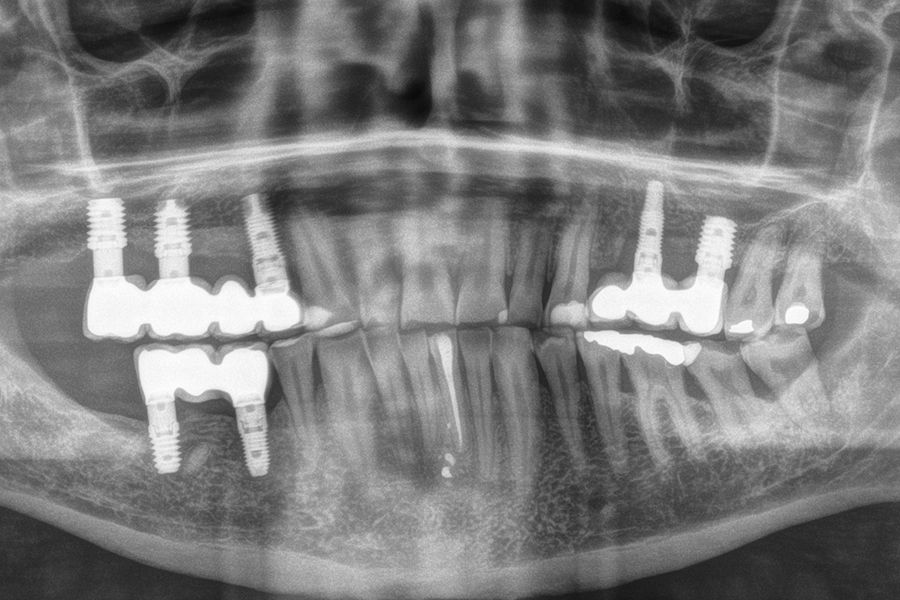

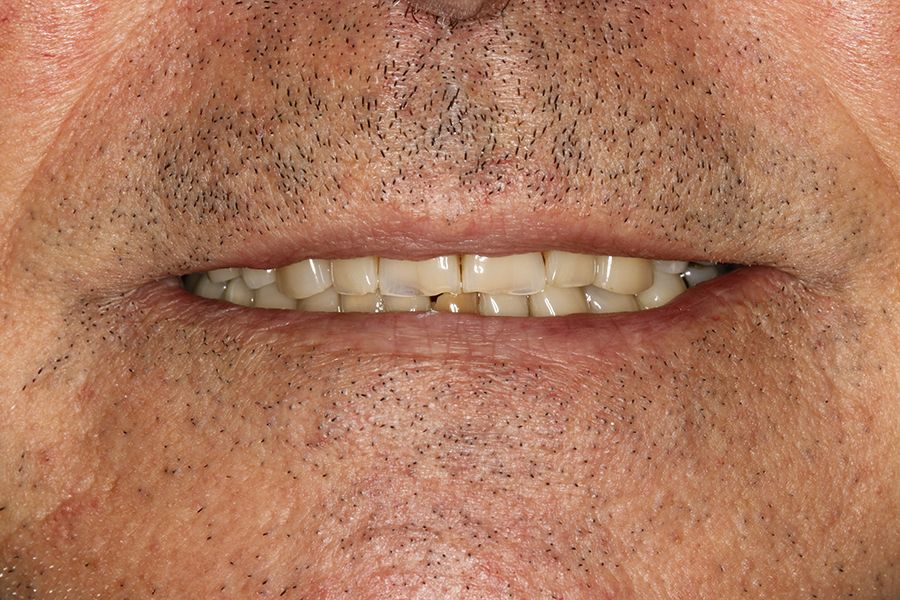

Figures 5–13 present one of the cases included in the

study.

Many patients with OSA exhibit oral signs and symptoms in addition to the classic features of systemic involvement.

Consequently, a comprehensive medical history and thorough assessment at the initial consultation

may enable the identification of individuals who

are unaware that they suffer from this serious health

condition, thereby facilitating the initiation of treatment11,12.

Moreover, for an extended period, we have encountered patients in dental clinics with a high incidence of dental, prosthetic, and even implant fractures without any apparent explanation, with the presence of sleep disorders frequently representing the causal factor sought11,12. Epidemiological studies have found a high prevalence of bruxism in patients with OSA37,11,12. Similarly, our group, in studying a series of patients with dental wear who were being treated with mandibular advancement devices for suspected sleep bruxism, found that 93% had sleep apnoea, which was mild to moderate in 56% and severe in 37%12. Furthermore, a dose-response relationship was observed. That is, greater severity of dental wear corresponded to increased severity of OSA. These findings suggest that dental health professionals are in an optimal position to identify patients with suspected OSA. Such suspicion may be inferred both through the use of clinical questionnaires and by identifying anatomical and/or functional alterations, as in the case of bruxism or fracture of prostheses

Once the patient has been diagnosed, it is of vital importance to initiate treatment for both processes:

the replacement of the rehabilitation affected by the

mechanical incident, and the commencement of OSA treatment with mandibular advancement devices or with CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure device) in more severe cases, where the device alone may not constitute a sufficiently effective treatment13,14. In certain situations, both approaches (CPAP and mandibular advancement device) may be combined, thereby reducing

the pressure required in CPAP, which in some cases

results in loss of adherence to treatment, or in those

bruxist patients where the mandibular advancement

device may enhance the maintenance of the teeth and the rehabilitations supported by them.

Bruxism and OSA are intimately related, as are the dental signs of both conditions, such as wear and fracture of teeth, implants, or rehabilitations. Dentists can play a fundamental role in the treatment of these patients, including the presumptive diagnosis of undiagnosed cases of OSA, which may be identified through dental problems.

Durán-Cantolla J, Puertas-Cuesta FJ,

Pin-Arboledas G, Santa María-Cano

J [Consensus national paper on sleep

apnea hypopnea syndrome.]. Archivos

de Bronconeumología 2005;41:1-110.

Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud

J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence

of sleep-disordered breathing among

middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med.

1993;328:1230-1235.

Lavigne GJ, Kato T, Kolta A, Sessle BJ.

Neurobiological mechanisms involved in

sleep bruxism. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med.

2003;14:30–46.

Kato T, Thie NMR, Hunyh N, Miyawaki

S, Lavigne GJ. Sleep bruxism and the

role of peripheral sensory influences. J

Orofac Pain. 2003; 17: 191–213.

Ohayon MM, Li KK, Guilleminault C. Risk

factors for sleep bruxism in the general

population. Chest. 2001;119:53-61.

Kato T. Sleep bruxism and its relation

to obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea

syndrome. Sleep Biol Rhythms.

2004;2:1-15.

Sjoholm TT, Lowe AA, Miyamoto K,

Fleetham JA, Ryan CF. Sleep bruxism in

patients with sleep-disordered breathing.

Arch Oral Biol. 2000; 45: 889-896.

Durán-Cantolla J, Alkhraisat MH,

Martínez C, Aguirre JJ, Guinea ER,

Anitua E. Frequency of obstructive

sleep apnea syndrome in dental patients

with tooth wear. J Clin Sleep Med.

2015;11:445-450.

Anitua E, Flores C, Durán-Cantolla J,

Almeida GZ, Alkhraisat MH. Frequency

of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Patients

Presenting with Tooth Fractures:

A Prospective Controlled Study. Int

J Periodontics Restorative Dent.

2023;43:121-127.

Anitua E, Durán-Cantolla J, Almeida

GZ, Alkhraisat MH. Association between

obstructive sleep apnea and enamel

cracks. Am J Dent. 2020;33:29-32.

Anitua E, Saracho J, Almeida GZ,

Duran-Cantolla J, Alkhraisat MH.

Frequency of Prosthetic Complications

Related to Implant-Borne Prosthesis in

a Sleep Disorder Unit. J Oral Implantol.

2017;43:19-23.

Durán-Cantolla J, Alkhraisat MH,

Martínez-Null C, Aguirre JJ, Guinea

ER, Anitua E. Frequency of obstructive

sleep apnea syndrome in dental patients

with tooth wear. J Clin Sleep Med.

2015;11:445-450

Durán-Cantolla J, Crovetto-Martínez

R, Alkhraisat MH, Crovetto M, Municio

A, Kutz R, et al. Efficacy of mandibular

advancement device in the treatment

of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: A

randomized controlled crossover clinical

trial. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal.

2015;20:e605-615.

Anitua E, Durán-Cantolla J, Almeida

GZ, Alkhraisat MH. Minimizing the

mandibular advancement in an

oral appliance for the treatment of

obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med.

2017;34:226-231.

Anitua, Eduardo

DDS, MD, PhD. Private practice in oral implantology, Eduardo Anitua Clinic Vitoria, Spain.

University Institute for Regenerative Medicine and Oral Implantology – UIRMI (UPV/ EHU Eduardo Anitua Foundation),

Vitoria, Spain. BTI Biotechnology institute (BTI), Vitoria, Spain.