Clinical cas

Published in spanish Científica Dental Vol. 18. Nº 2. 2021 www.cientificadental.es

The challenge of the surgical approach in the rehabilitation of an anterior sector unitary implant in a case of high aesthetic requirements; case report

Objective: Provide a detailed description of the current evidence-based clinical approach to a post-extraction implant with immediate loading and provisionalisation.

Clinical case: A 32-year-old female patient who attended for a possible root fracture of the upper left central incisor (ULCI), accompanied by a periodontal abscess at the bottom of the vestibule of the same tooth. A clinical and radiological examination established that the prognosis of the ULCI was unfavourable for conservative treatment. After evaluating the clinical features of the case, the treatment plan to extract the ULCI followed immediately by an osseointegrated implant (OII) and loading of a provisional prosthesis on the implant.

Conclusions: Rehabilitation on implants in situations of tooth loss in the aesthetic anterior sector, especially in young patients, requires a multidisciplinary treatment plan to extract the tooth and insert an OII in the correct 3-dimensional position. Various aspects need to be taken into account for this, particularly the residual remaining bone, the position of the gingival margin and preservation and conditioning of the peri-implant hard and soft tissues by means of grafts and proper handling of provisional prosthesis, until an ideal emergence profile and gingival contour is achieved before the final crown.

Oral biology has become more important in the 21st century, since it is necessary to highlight the processes related to bone and soft tissue biology, the loss of a tooth and the future of tissues after their replacement with a dental implant.

The physiological processes that take place after the extraction of a tooth are drastic, as they entail a series of modifications in the soft and hard tissues of the alveolar complex. Mainly, the microvascularisation of the architecture that surrounds the tooth suffers damage and atrophy that culminates in a decrease in the vascular supply provided by the periodontal ligament1-4. This results in a series of resorption processes discussed in this description of a clinical case.

Advances in oral implantology have brought with it new surface treatments for osseointegrated implants (OII), as well as different macroscopic designs and materials. This has been associated with greater primary stability of the OII and a better prognosis. The current trend in the field of implantology has been an evolution from conventional loading of the OII to immediate loading, due to the greater functional and aesthetic demands of society and patients5.

The benefits of immediate loading include a marked reduction in surgical interventions, less temporary dilation of the treatment and even better psychological and social wellbeing for the patient. In cases with a significant aesthetic requirement, immediate loading or provisionalisation, and post-extraction placement of the OII minimise alterations due to tooth loss and maintain the emergence profile, soft tissue contour and gingival papillae5-7.

Different protocols have also been established for the management of the anterosuperior aesthetic sector, in addition to performing the immediate implant and provisional crown, including placing material between the OII and the buccal cortical to minimise possible collapse and the management of peri-implant soft tissue8-11.

The objective of this article is to provide a detailed, evidence-based description of the clinical approach to a post-extraction implant with immediate loading and provisionalisation.

We present the case of a 32-year-old female patient referred by her dentist to the Master’s of Oral Surgery and Implantology at Rey Juan Carlos University for a possible root fracture of the upper left central incisor (ULCI), accompanied by a periodontal abscess at the bottom of the vestibule region of the tooth.

The patient reported no allergies or drug use for the treatment of diseases and had no -surgical history. She was an ASA class I patient with no smoking or alcohol habits reported.

Examination and diagnosis

The patient’s symptoms were pain in the anterosuperior area after chewing that disappeared after the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory analgesic drugs.

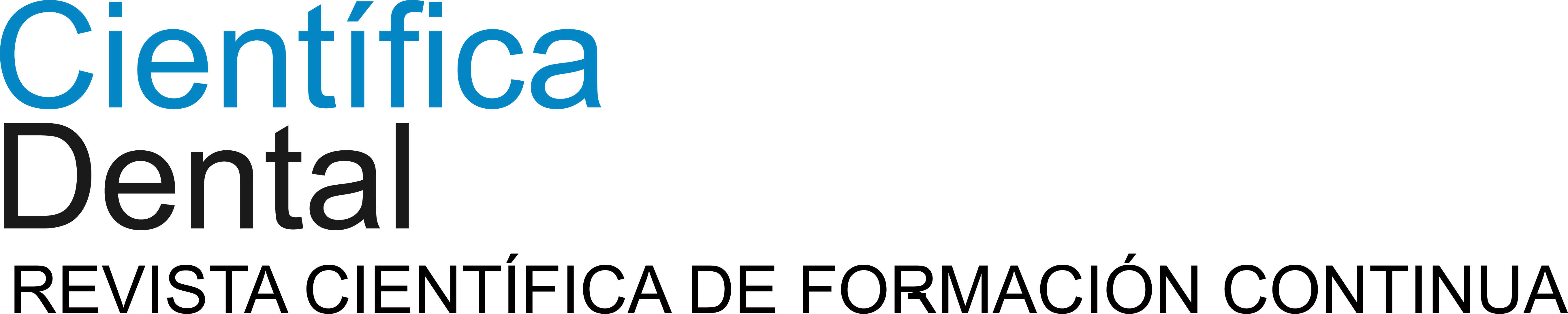

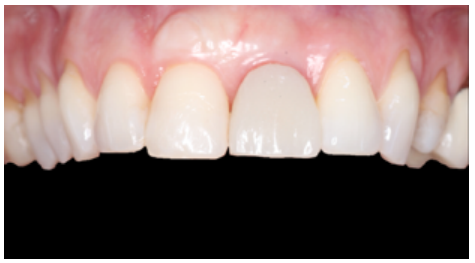

At the intraoral level, a mid-smile line and fine gingival biotype was observed, accompanied by gingival recessions at the level of the upper right central incisor (URCI), as well as in the first, third and fifth sextant teeth. There was slight crowding in the lower anterior region and evidence of multiple dental treatments, such as root canals and osseointegrated implants (OII).

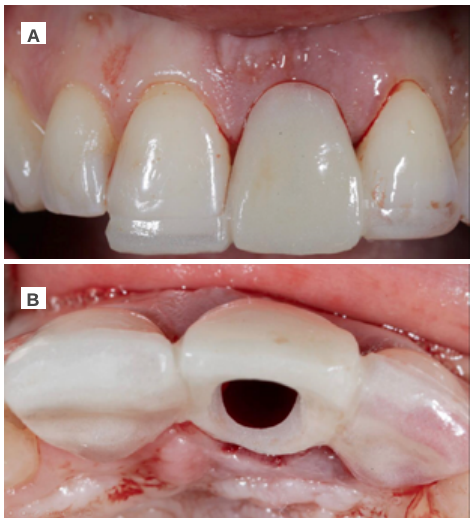

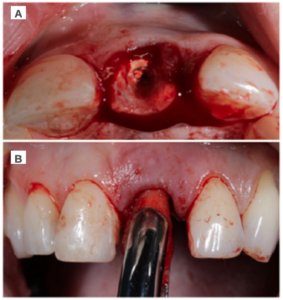

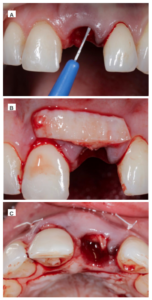

Erythematous mucosa was observed In the ULCI region, accompanied by inflammation of the apical region of the tooth at the level of the attached gingiva, suspected to be due to a periapical abscess following infection of the tooth (Figure 1). The ULCI had great mobility due to a radicular fracture not observed on clinical examination.

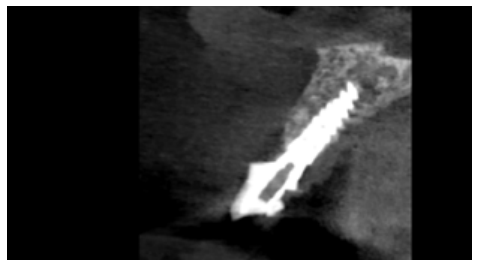

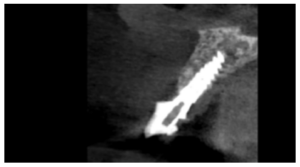

A radiological examination was carried out that included a periapical radiograph and a CBCT to appreciate the distribution of the ULCI fracture better (Figure 2).

The radiographic examination confirmed an oblique fracture that included the region of the middle third of the root and extended in a coronal-palatal direction towards the coronal region. Likewise, the presence of normal root canal treatment and the absence of a vestibular plate in the region of the two coronal thirds of the ULCI root was observed.

Prognosis

After carrying out a clinical and radiological examination, it was established that the prognosis was unfavourable for conservative treatment of the ULCI. After evaluating the clinical features, a treatment plan was established based on extracting the ULCI with immediate placement of a post-extraction OII and loading with a provisional prosthesis.

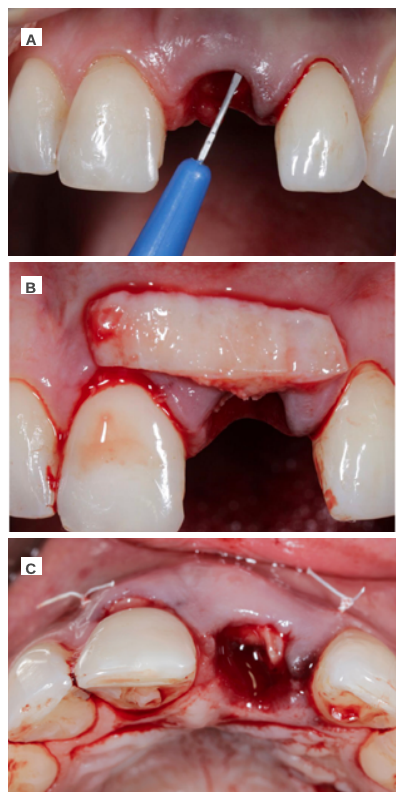

Surgical approach

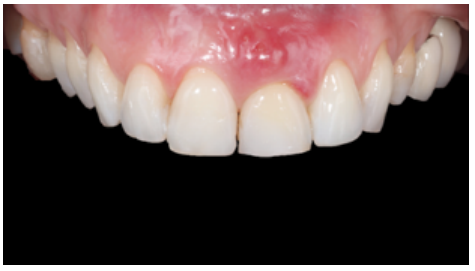

Under local anaesthesia (articaine 4% 1:100,000 adrenaline) with an infiltrative technique at the level of the vestibular fundus of the maxillary anterior region (anterior superior alveolar nerve) and palatine region (nasopalatine nerve), the coronal fragment of the ULCI was extracted before taking out its root (Figure 3A). A syndesmotomy of the surrounding soft tissue was performed for this, to establish the condition of the vestibular cortical bone by palpation. After that, the root was extracted in a controlled manner to minimise trauma, by first dislocating it with a periotome and subsequent controlled gripping with forceps (Figure 3B).

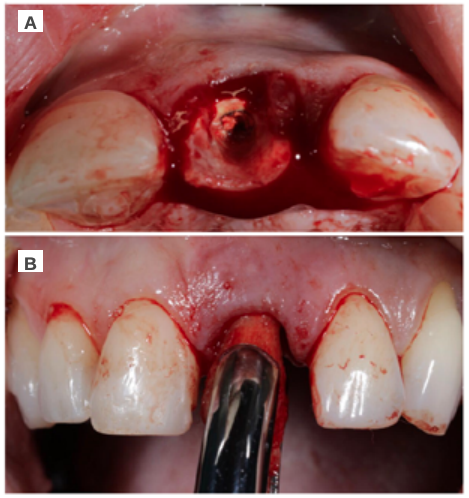

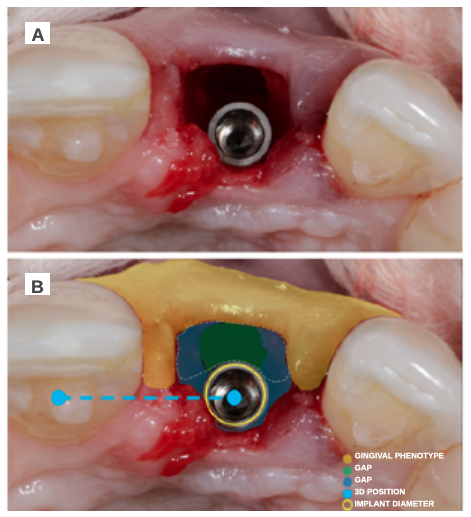

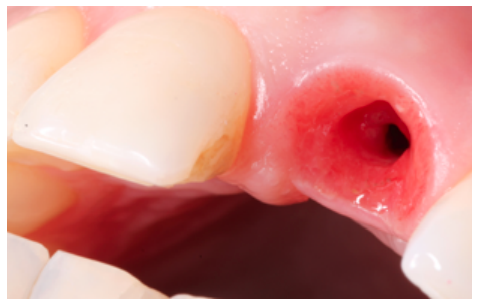

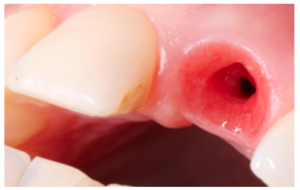

Using a Lucas-type curette spoon and a CP12 periodontal probe, the state of the alveolus was checked and found to be completely intact, except for the vestibular region, where there was a defect in the coronal-apical direction of 4 mm (Figure 4).

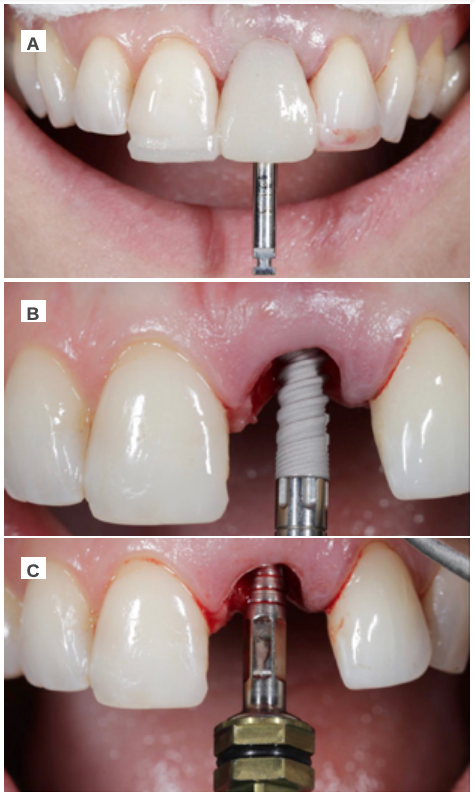

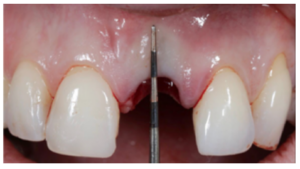

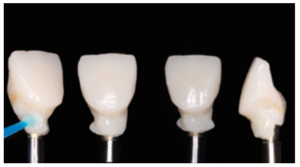

The provisional Maryland-type prosthesis was used as a provisional device and surgical guide to guarantee the correct vestibulo-lingual position of the OII, according to the plan devised, thus preventing any future problems at the prosthodontic level or in the integrity of the soft and hard tissues of the vestibular region (Figures 5A and 5B).

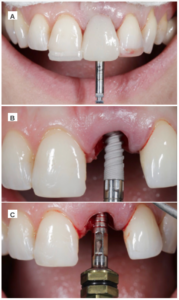

The drilling protocol was followed for the placement of the OII through the surgical guide, with its correct 3-dimensional position being checked at all times (Figures 6A, 6B and 6C).

A. Arrangement of the initial surgical drill.

B. Insertion of the dental implant after drilling guided by the provisional prosthesis as a surgical guide.

C. Manual establishment by an implant carrier of the ideal coronal-apical position for the correct evolution of the future prosthesis and soft and hard tissues.

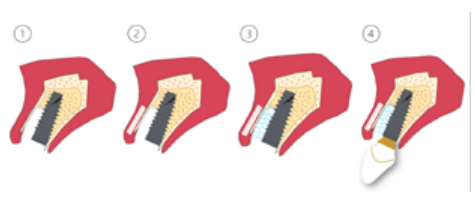

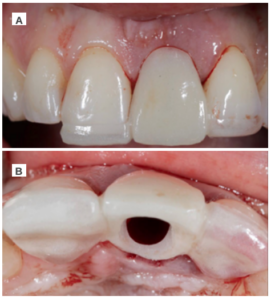

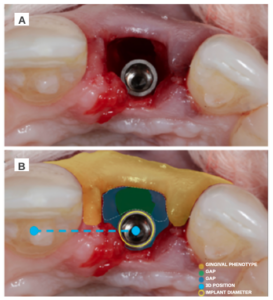

The OII (Neo AlphaBio Medical10™ 3.25mm x 11mm) was inserted at a depth with respect to the future gingival margin that needed to be achieved, 4 mm away from the shoulder of the OII. In this case, the reference gingival margin was that of the ULCI itself, since it was intact and unchanged; while, in the case of the URCI, there was a gingival recession of 2 mm. In this process, the choice of OII diameter was taken so that a space or “gap” would be obtained to facilitate reconstruction of the vestibular cortical bone, paying special attention to the gingival phenotype, to allow for management of the soft tissues also (Figures 7A and 7B).

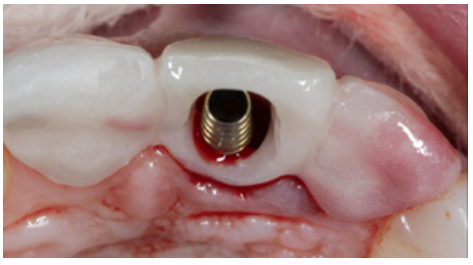

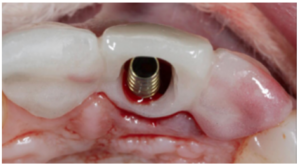

Primary stability was obtained, achieving anchorage in the palatal residual bone at an insertion torque of 35 N/ cm2 . Subsequently, a temporary prosthetic abutment was placed.

Provisional prosthetic phase

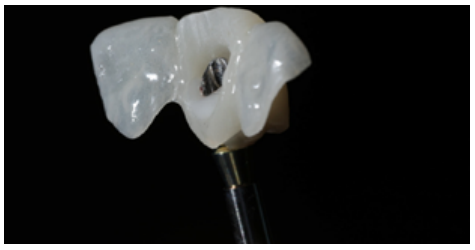

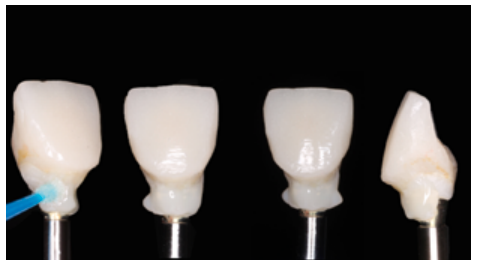

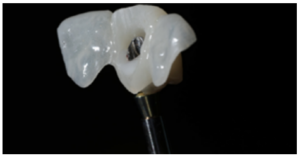

Before starting the provisional screw-retained restoration on the OII, the correct position of the abutment in terms of the provisional prosthesis was verified. The abutment was relined with the provisional through the use of flowable composite (Figures 8 and 9).

Preparation of the emergence profile

To perform the emergence profile (EP), the ideal position of the gingival margin was determined, which had to coincide with the position of the cervical line (amelocemental junction) of the ULCI (Figures 10-13B).

Soft and hard tissue management

In these types of cases, the management of hard and soft tissues takes on special importance.

The recipient area was prepared for the approach using the pouch and tunnel technique. A full-thickness incision was made through the vestibular region of the alveolus resulting from the extraction. This fan incision was made with the use of a crescent knife and tunneller. The corona region of the incision was made at full thickness, but the mesial and distal region that compromised the inserted mucosa of teeth 22 and 11 were made at partial thickness; this same plane was maintained in the apical region of the ULCI area.

The donor area was then approached, for which a graft was taken that comprised epithelial tissue and connective tissue (free gingival graft), approximately 2.5 mm thick from the palatal region of the left hemimaxilla, encompassing the premolar and molar region of this zone. This approach was chosen due to the greater guarantees regarding the quality of the connective tissue graft (CTG) when its de-epithelialisation takes place outside the mouth due to the maintenance of the lamina propria.

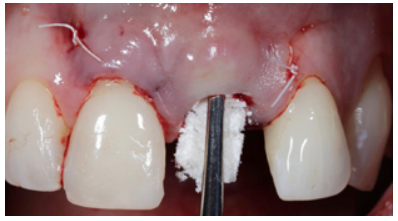

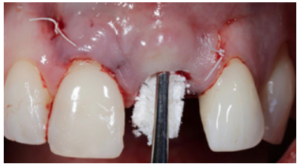

Due to a 2 mm gingival recession in the URCI, the CTG obtained was of sufficient size to encompass the region of this tooth and to be able to treat this recession simultaneously with the OII procedure. It was adapted to the recipient region with a 5.0 polytetrafluorethylene (PTFE) suture with mesial and distal fixation points, which guaranteed proper vascularisation of the graft (Figures 14A, 14B and 14C).

Subsequently, to guarantee the stability of the soft tissues and to anticipate the remodelling of the hard tissue resulting in vestibular defects, bone preservation of the vestibular region of the alveolus was carried out. A collagen-reinforced bone xenograft (Bio-Oss™ Collagen, Geistlich) was used, which was placed in the gap between the vestibular cortical bone and the implant itself (Figure 15).

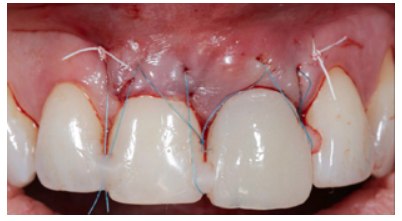

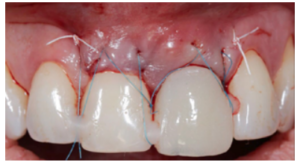

To complete the surgical approach, the provisional prosthesis was placed with the already made PE and 3 points of coronal traction were carried out, anchoring them to the contact points of the provisional and adjacent teeth with a 6.0 monofilament suture (Figure 16).

Evolution

The first review of the surgical procedure was carried out 7 days later. Proper initial healing of the soft tissues and a lack of infectious or inflammatory pathology were observed (Figure 18). At 14 days, a second review was performed when the suture was removed (Figure 19). The review one month after surgery showed proper initial stability of the soft and hard tissues, as well as the absence of any signs related to the failure of the procedure (Figure 20).

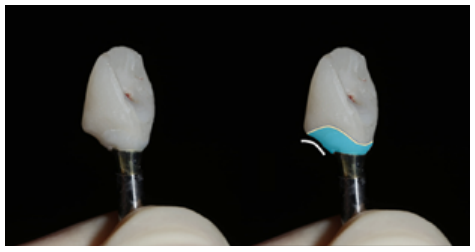

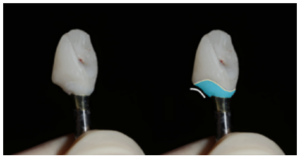

At 4 months, good stability of the OII was seen as a result of the proper osseointegration process. For the soft tissues, a decrease in the volume of the interdental papilla could be seen (Figure 21). Given the absence of signs and symptoms and the proper osseointegration of the OII, the subcritical profile was modified to improve the arrangement of the gingival soft tissue and promote recovery of this papilla (Figures 22 and 23).

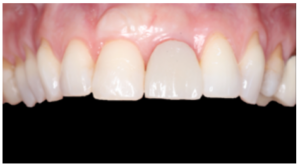

At 6 months, proper arrangement of the soft tissues could be seen, with their stability over time due to their handling through the provisional prosthesis (Figure 24).

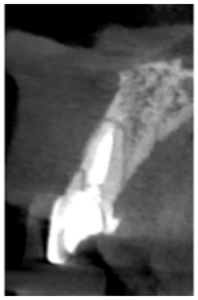

A radiological check was also carried out to determine the status of the hard tissues (Figure 25).

Given the good evolution at 6 months, the position of the OII and the emergence profile were recorded via an individualised transfer to replicate the gingival architecture faithfully and in detail (Figures 26 and 27). The final fixed prosthesis screwed to the OII was inserted 7 months after the treatment had started (Figures 28 and 29).

The current trend in the field of implantology has been an evolution from conventional loading of the OII to immediate loading, due to the greater functional and aesthetic demands of society and patients12,13.

The benefits of immediate loading include a notable reduction in surgical interventions, a shorter time delay in treatment and better psychological and social wellbeing for the patient12

Among the success factors that influence immediate loading are the primary stability of the implant, the presence of micromovements, the surface and size of the implant, the quantity and quality of bone, the insertion torque, the occlusion, patient habits, local and systemic factors and the type of prosthodontic rehabilitation12,13.

Some authors believe that micromovements of less than 30 microns do not influence the osseointegration phase of the OII, with it being suggested that micromovements up to 100 microns have no negatively effects; in fact, movements of 60- 90 microns can promote higher bone density around the OII. The insertion torque of the OII must be at least 30-40 N// cm2. 12-14.

These requirements for implant loading generally become more difficult to obtain when the implant is placed in a socket immediately after tooth extraction, due to less residual bone presence. The immediate or early placement of an OII is widely supported by the literature, with no significant differences during osseointegration. Therefore, the placement of a postextraction implant and, in turn, its immediate loading, represent a considerable reduction in treatment times while obtaining immediate aesthetic benefits and function12-15.

To date, there are studies that highlight the greater risk of failure in single implants subjected to immediate loading compared to multiple implant restorations, even obtaining a high insertion torque. Therefore, the concept of “loading” has changed to that of “provisionalisation”, since the provisional crown is completely exempt from function. The importance of these provisional restorations, in addition to immediate aesthetic benefit, lies in the maintenance of the emergence profile similar to the anatomy prior to extraction, as well as the gingival contour and interdental papillae; thus favouring the maintenance of volume and reducing collapse due to tooth loss12-15.

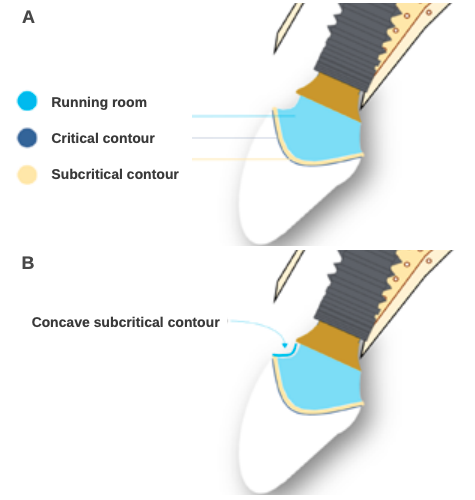

According to different studies, these restorations also stabilise the clot that minimises the loss of the cortical bone of the vestibular region when combined with non-resorbable grafts. The modification of the critical and subcritical contour, concepts described by Su et al. in a second phase, prior to making the final prosthesis, allow the gingival contour to be shaped until the ideal architecture and aesthetics are achieved16.

Regarding the placement of graft material in the gap between the implant and the vestibular bone, there are studies that support the use of a non-resorbable bone graft due to contributing to compensating for the contraction of the marginal ridge; thus preserving the alveolar contour prior to tooth extraction to a greater extent.. A gap greater than 2-3 mm between the OII and the vestibular cortical bone would facilitate the formation of a blood clot that would subsequently differentiate into new bone. Studies comparing filling and not filling the gap with different materials (autologous bone, xenograft or alloplastic grafts) have highlighted significant differences in terms of less vestibular collapse in the study groups in which a sufficient gap was respected for clot formation next to the graft with a non-resorbable material, such as xenogenic or alloplastic materials based on hydroxyapatite.

A summary of the essential points to consider for the placement of post-extraction implants in aesthetic cases follows:

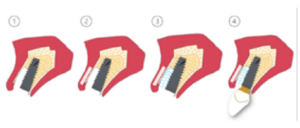

Residual bone

This is the key point for the placement of the OII. It can be inserted if there is sufficient residual bone to place and prosthetically guide it in the correct 3-dimensional position. In the anterior sector, the area corresponding to the apico-palatal zone of the alveolar bone is the anchorage region for the OII. According to Kan et al., 81% of the alveoli (class I alveoli according to their classification) have a sufficient amount of apicalpalatal bone to insert the implant in an ideal prosthetic position22. Not having sufficient residual bone in the ideal prosthetic position contraindicates the treatment, and alveolar preservation or reconstruction with delayed placement of the OII7 would have to be considered.

Gingival margin

In cases where there is a recession greater than 4 mm, it will be decided to defer the immediate placement of the implant, since this situation is accompanied by a complete or almost complete defect of the vestibular cortical bone, which must be reconstructed beforehand. This is because there is also usually significant soft tissue loss which will decrease the predictability of the treatment. Authors such as Da Rosa et al. have proposed the vestibular reconstruction technique of hard and soft tissue at the same time as immediate placement of the OII. However, this is a complex technique, dependent on the donor area, and there is currently not enough scientific literature to evaluate its results23.

Defects in the vestibular cortical

As long as the previous points are favourable, any fenestrations or dehiscences in the vestibular cortical bone will not contraindicate immediate placement of the implant with its subsequent provisionalisation. If there are significant defects of more than 5 mm, in addition to the graft material in the vestibular gap, a native collagen membrane between this graft and the soft tissue will need to be interposed, according to different studies, to promote proper regeneration of the vestibular bone volume and prevent the invasion of epithelial cells19,24.

Periodontal phenotype

The knowledge and importance of the quality of the periodontium, and, therefore, of the soft tissue surrounding the tooth or implant, has undergone a metamorphosis over time. Some authors have already found that the morphology of the dental crown and the clinical features of the periodontium have a certain relationship25. The same author had previously observed that certain forms of the clinical crown were closely related to the appearance of gingival recessions, especially in cases where the crown coincided with an elongated and narrow appearance, compatible with what today would be a thin gingival biotype25.

However, the last workshop on the classification of periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions in 2017 suggested the periodontal phenotype – a term that encompasses gingival phenotype (gingival volume) and bone morphotype (thickness of the vestibular cortical bone) – as the best way to evaluate the different aspects around the old term of gingival biotype. There are certain aspects of the gum that are not limited to gingival thickness, but that bone volume is also a determining factor. In the present clinical case, during the periodontal probing, the probe was visible, which suggests a thickness of less than 1 mm and a discrete volume of the vestibular bone region was observed in the tomographic study26,27.

This periodontal aspect had been studied previously in a publication by Müller et al., in which it was indicated that the “gingival phenotype” responded to the dental shape, again to the gingival biotype and the degree of keratinisation of the gingiva28.

A notable feature of soft tissue that has not yet been conclusively revealed in the scientific literature is whether the presence of tissue with a certain degree of keratinisation around the implant is a prognostic factor for it. The clinical evidence may be suggestive of this, as seen in clinical studies from the 1990s28; although current systematic reviews have not highlighted the results of these clinical studies29. There should be further in-depth study of this aspect; however, a recent study suggests that the presence of more than 1 mm of keratinised gingiva is not a significant factor in the probability of the appearance of peri-implantitis, giving the prominence of the appearance of this pathology to other factors30.

That is why this clinical case raises special complexity if the aspects present regarding the patient’s periodontal phenotype are considered, whose features imply proper management of the soft tissues, evaluating the placement of a connective tissue graft simultaneously with the placement of the OII. The latter is to prevent the appearance of soft tissue defects in the long term and, therefore, aesthetic complications and those of the implant itself that may occur in the future31,32.

Rehabilitation on implants in dental loss situations in the aesthetic anterior sector, especially in young patients, requires a multidisciplinary treatment plan for tooth extraction and placement of the OII in the proper 3-dimensional position, with different aspects to be taken into account for this. Especially important are the residual bone present, the position of the gingival margin and the preservation and conditioning of the peri-implant hard and soft tissues. This is done by means of grafts and proper handling of a provisional prosthesis, until an emergence profile and ideal gingival contour are achieved before the final crown.

Araújo MG, Lindhe J. Dimensional ridge alterations following tooth extraction. An experimental study in the dog. J Clin Periodontol 2005; 32 (2): 212-8.

Araújo MG, Sukekava F, Wennström JL, Lindhe J. Ridge alterations following implant placement in fresh extraction sockets: an experimental study in the dog. J Clin Periodontol 2005; 32 (6): 645-52

Araújo MG, da Silva JCC, de Mendonça AF, Lindhe J. Ridge alterations following grafting of fresh extraction sockets in man. A randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Implants Res 2015; 26 (4): 407-412.

Araújo MG, Sukekava F, Wennström JL, Lindhe J. Tissue modeling following implant placement in fresh extraction sockets. Clin Oral Implants Res 2006; 17 (6): 615-24.

Cheng Q, Su YY, Wang X, Chen S. Clinical Outcomes Following Immediate Loading of Single-Tooth Implants in the Esthetic Zone: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2020; 35 (1): 167-177.

Elian N, Cho SC, Froum S, Smith RB, Tarnow DP. A simplified socket classification and repair technique. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent 2007; 19 (2): 99-104.

Uribe R, Peñarrocha M, Balaguer J, Fulgueiras N. Immediate loading in oral implants. Present situation. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2005; 10 (2): E143-53.

Araújo M, Linder E, Wennström J, Lindhe J. The influence of Bio-Oss Collagen on healing of an extraction socket: an experimental study in the dog. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2008; 28 (2): 123-35.

Araújo MG, da Silva JCC, de Mendonça AF, Lindhe J. Ridge alterations following grafting of fresh extraction sockets in man. A randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Implants Res 2015; 26 (4): 407-412.

Sanz M, Lindhe J, Alcaraz J, SanzSanchez I, Cecchinato D. The effect of placing a bone replacement graft in the gap at immediately placed implants: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Implants Res 2017; 28 (8): 902-910.

Chen ST, Buser D. Clinical and esthetic outcomes of implants placed in postextraction sites. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2009; 24: 186-217.

Higginbottom F, Belser R, D. Jones J, E. Keith S. Prosthetic management of implants the esthetic zone. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac Implants 2004; 19: 62-72.

Al-Sabbagh M. Implants in the Esthetic Zone. Dent Clin N Am 2006; 50: 391–407.

Buser et al. Optimizing esthetics for implant restorations in the anterior maxilla: anatomic and surgical considerations. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac Implants 2004; 19: 43-61.

Buser D, Chappuis V, Belser UC, Chen S. Implant placement post extraction in esthetic single tooth sites: when immediate, when early, when late? Periodontol 2000 2017; 73 (1): 84-102.

Su H, González-Martin O, Weisgold A, Lee E. Considerations of implant abutment and Crown contour: Critical contour and subcritical contour. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2010; 30: 335-343

Strub JR Jurdzik BA, Tuna T. Prognosis of immediately loaded implants and their restorations: a systematic literature review. J Oral Rehabil 2012; 39 (9): 704-17.

Araújo M, Linder E, Wennström J, Lindhe J. The influence of Bio-Oss Collagen on healing of an extraction socket: an experimental study in the dog. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2008; 28 (2): 123-35

Noelken R, Geier J, Kunkel M, Jepsen S, Wagner W. Influence of soft tissue grafting, orofacial implant position, and angulation on facial hard and soft tissue thickness at immediately inserted and provisionalized implants in the anterior maxilla. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2018; 20 (5): 674-682.

Zurh O et al. Clinical Benefits of the Immediate Implant Socket Shield Technique. J of Esthet Restor Dent 2017; 29 (2): 93-101.

Fu JH et al. Influence of tissue biotye on implant esthetics Int. J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2011; 26: 499-508.

Kan JY, Roe P, Rungcharassaeng K, Patel RD, Waki T, Lozada JL, Zimmerman G. Classification of sagittal root position in relation to the anterior maxillary osseous housing for immediate implant placement: a cone beam computed tomography study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2011; 26 (4): 873-6.

Martins-da Rosa JC, de Oliveira-Rosa AC, Fadanelli MA, Sotto-Maior B. Immediate implant placement, reconstruction of compromised sockets, and repair of gingival recession with a triple graft from themaxillary tuberosity: A variation of the immediate dentoalveolar restoration technique. Prosthet Dent 2014; 112: 717-722.

Influence of tissue biotye on implant esthetics Int. J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2011; 26: 499-508.

Olsson M, Lindhe J, Marinello CP. On the relationship between crown form and clinical features of the gingiva in adolescents. J Clin Periodontol 1993; 20 (8): 570-7.

Chapple ILC, Mealey BL, Van Dyke TE, Bartold PM, Dommisch H, Eickholz P y cols. Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: Consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol 2018; 89 (1): S74-S84.

Papapanou PN, Sanz M, Buduneli N, Dietrich T, Feres M, Fine DH y cols. Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Clin Periodontol 2018; 45 (20): S162-S170.

Müller HP, Eger T. Gingival phenotypes in young male adults. J Clin Periodontol 1997; 24 (1): 65-71.

Wennstrom JL, Derks J. Is there a need for keratinized mucosa around implants to maintain health and tissue stability? Clin Oral Implants Res 2012: 23: 136–146.

Vignoletti F, Di Domenico GL, Di Martino M, Montero E, de Sanctis M. Prevalence and risk indicators of peri-implantitis in a sample of university-based dental patients in Italy: A cross-sectional study. J Clin Periodontol 2019; 46 (5): 597-605.

Thoma DS, Mühlemann S, Jung RE. Critical soft-tissue dimensions with dental implants and treatment concepts. Periodontol 2000 2014; 66 (1): 106-18.

Bassetti RG, Stähli A, Bassetti MA, Sculean A. Soft tissue augmentation around osseointegrated and uncovered dental implants: a systematic review. Clin Oral Investig 2017; 21 (1): 53-70.

Peña Cardelles, Juan Francisco

Lecturer for the Master’s in Oral Surgery and Implantology, Rey Juan Carlos University.

Asensio Acevedo, Ramón

Master’s in Oral Surgery and Implantology, Rey Juan Carlos University.

Ortega Concepción, Daniel

Lecturer for the Master’s in Oral Surgery and Implantology, Rey Juan Carlos University.

Moreno Pérez, Jesús

Lecturer for the Master’s in Oral Surgery and Implantology, Rey Juan Carlos University

Robles Cantero, Daniel

Lecturer for the Master’s in Oral Surgery and Implantology, Rey Juan Carlos University

García Guerrero, Iván

Lecturer for the Master’s in Oral Surgery and Implantology, Rey Juan Carlos University.

Gómez de Diego, Rafael

Lecturer for the Master’s in Oral Surgery and Implant